Every Word's Hidden Meaning

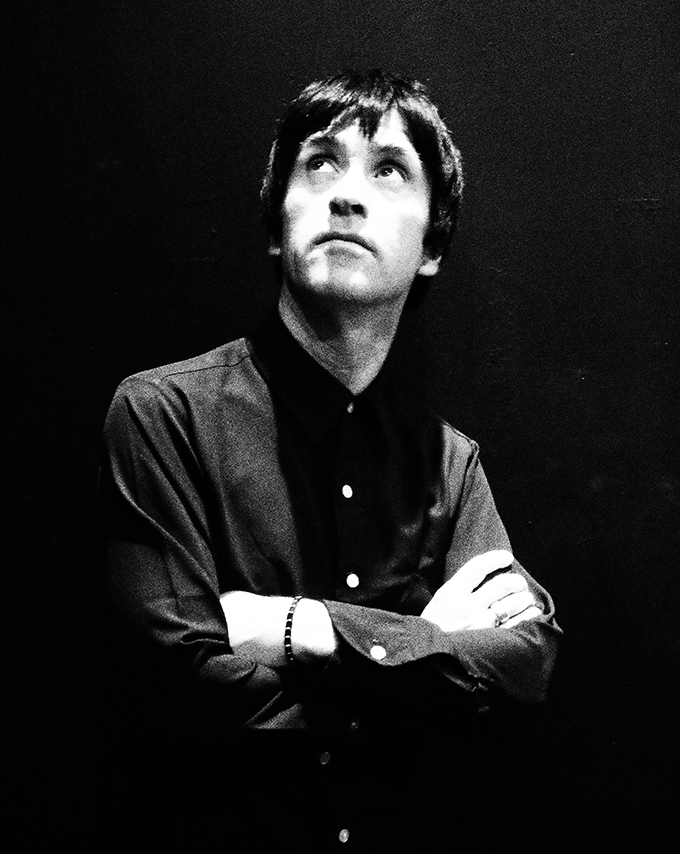

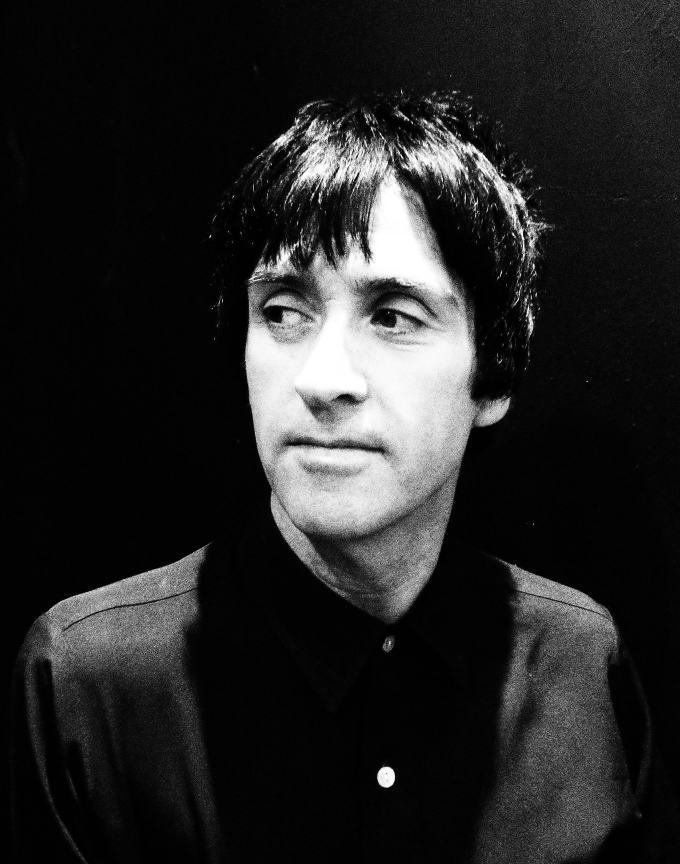

Johnny Marr is a man of many talents. Though renowned first and foremost as a staggeringly gifted guitarist and composer, he's also a highly competent lyricist; prose writer; style icon...and a naturally gifted conversationalist.

There's never a need to worry about awkward silences when talking to Johnny. He can articulately converse for hours on topics as wide-ranging as music, philosophy, politics ('with a small p'), art and literature, and is never, ever boring. Not only does he like to talk, but he's bloody good at it. 'I don't think anyone's as good at anything as I am at talking,' Johnny says playfully, a cheeky grin lighting up his handsome features. And he could very well be right.

Despite having spent more than thirty years in the spotlight now, and given countless interviews, Johnny exhibits very little hostility towards the press. 'I think I get a fair enough shake,' he concedes. 'But most people I talk to are alright and the solo records have been very well received, so I don't have a problem. Some journalists can come with an agenda and think they're going to get under my skin by asking about The Smiths and therefore get some kind of scoop or something, but that would be flattering themselves. It doesn't happen too much.'

Both Playland and its precursor The Messenger have been met with overwhelmingly positive reactions from the press, and the past few years since launching his solo career have seen journalists the world over clamouring for a chat with the iconic Mancunian guitarist. For Johnny though, the opinions that matter most are that of his own fan base.

'I want my audience to like what I put out,' he says. 'That sounds very obvious, but it doesn't have to be an automatic consideration for a band or artist. You could have a different agenda.'

'I like my audience,' Johnny continues. 'It's interesting to me to know what some of them do and what they're about sometimes. Social Media is somewhat of a mixed bag - it's not all good news, but I've had some nice experiences and that's been cool. Also, what's the alternative to being nice to fans...being nasty? That doesn't sit right with me. Never has. I've always thought the fans were really important.'

'There are things that happen that are very touching. I've had people make marriage proposals during the show, and there's a young guy with autism who comes to hang out with us sometimes. He gets on Jack's kit at soundchecks and the pleasure he gets from that is really nice to see. Having someone name their child after you is a real honour, of course. There are a lot of people with "There Is A Light That Never Goes Out" on their bodies, and I'm amazed when people get a picture of me tattooed on themselves. Some people travel from all over the world. Mostly, I like to see people losing themselves in the show. That's the best thing.'

Johnny's audience is an interesting mix. Some are veteran Smiths fans who have followed his career right from the start; others have been introduced to Johnny's music through more recent former bands such as Modest Mouse and The Cribs. Another even newer category of fans are young people who have been initiated into the World Of Marr through his recent solo records: those who know him first and foremost as "Johnny Marr", not "Johnny Marr of The Smiths", although many go on to discover much of his back catalogue as well.

'It's really touching and gratifying to see very young people at the shows,' Johnny says. 'They're usually there totally because they love the music, all of it. It doesn't matter how they got into it, and there's all kinds of reasons, but it's definitely not because of some hype. It's always a personal connection of some sort to the music or to me, so that's quite special.'

Inevitably, Johnny has attracted his fair share of youthful admirers. It's an everyday occurrence to see young (often - but not always - female) fans expressing declarations of romantic attraction towards the 51-year-old guitarist via social media, and quite frequently even in messages directed at Johnny himself. Though other artists in his position might feel somewhat uncomfortable with being seen as an object of desire in the eyes of people even younger than his own children, Johnny is refreshingly unperturbed. 'I just put it down as an aspect of fame, people projecting things, for whatever reason,' he explains. 'I've never analysed that. It's beyond analysis, really.'

Beyond analysis such things may be, but being able to relate to his audience, regardless of their age, gender or lifestyle, seems of paramount importance to Johnny.

'I like to think that my audience have some of the same sensibilities. I realise that from a young age I've lived a very different life to most people, but people's values can be alike, even if it's just musically. I think the audience know my ideology,' Johnny says, although he also makes a point to explain: 'I don't mind if people just like me for my guitar playing though. That's fine. I'm happy that the fans like what I do for whatever reason they like.'

'I will say this though,' he adds. 'I don't think the lyrics are obscure. Far from it. I just don't go around advertising the concepts.'

As a solo artist, Johnny has proven himself to be more than just a gifted guitarist and composer: he's also a talented lyricist, whose words are profound and poetic without resorting to the sort of clicheéd, self-indulgent omphaloskepsis that seems to be in vogue with the current indie crowd. Johnny's lyrics tend to be inspired by observation rather than introspection, and as a result his sources for inspiration are practically infinite. Heightened imagination, he says, is the primary benefit of choosing to write about external situations rather than his own emotions.

'There's more for me to imagine than if I'm expressing my own feelings. Ultimately whatever you write is a reflection of yourself and how you perceive things. I'm not particularly interested in expressing my opinions as such at this point, and everyone seems to be doing that. I'd rather observe external things. Someone has to do it.'

'I like to make the lyrics more observational than introspective,' he continues. 'I'm usually on alert for inspiration and sometimes something might jump out at me from a conversation between people, or an article somewhere about something. It's enjoyable when I'm not looking and a phrase or word or concept surprises me. Inspiration doesn't strike so much if you're trying too hard. It's what artists need to live.'

One particular recurring concept in Johnny's lyrics is that of escapism. Escapism through music; through technology; through sex. Even beyond Johnny's lyrics, it's a theme so strong and so prevalent that it can't help but make one question: what is it that so many people are trying to escape from? And where are they hoping to escape to?

'Chasing after escapism through entertainment, consumerism and physical sensation, amongst other things, seems to be the social norm,' Johnny explains. 'Entertainment through the big night out, consumerism through rinsing the credit card and physical sensation through alcohol culture or sexual preoccupation is always there. I'm a product of the culture myself and I'm involved the same as everyone,' he acknowledges, 'So I'm not judging. But I'm wondering if it's because we've stopped knowing how to be with ourselves? Maybe people aren't okay with themselves. Even if you're self-aware you can still suffer a certain malaise, which is what "This Tension" is about. I did think it was important to celebrate escapism though, in songs like "Back In The Box" and "Playland", to express the other side of it. Those songs are tributes to transcendence, mostly through music and sex.'

Hearing him speak so articulately about his ideas and inspirations, it comes as no surprise when Johnny admits he's been writing lyrics almost all his life.

'I started writing lyrics when I was about fourteen or fifteen,' he tells me. 'The first lyrics I wrote when I was ten or eleven, but I think they might have been a bit immature. I never didn't write entirely. Even in The Smiths I wrote bits of prose sometimes, just for myself.'

Intrigued, I ask what was the first song Johnny ever wrote a full set of lyrics to.

'That would've been when I was eleven, for my first band. I don't remember the title but it was about not liking school and getting the hell out. Some things don't change, thank god.'

Interestingly, it was those schooldays that inspired Johnny's most autobiographical song to date. "25 Hours", with lyrics such as 'And the heat and the bricks / Were falling on me like doom', paints an understandably bleak picture of not only education in Manchester in the 1970s, but the brutality of the Catholic church.

'The Catholic religion hasn't exactly made itself very credible over the last twenty five years or so, has it?' Johnny muses. 'Anyone who was brought up around priests and nuns will tell you it was sadistic, and worse.'

His feelings about Catholicism quite clear, I'm admittedly curious to know: Does Johnny Marr believe in God?

'Bloody hell,' is his initial response to such a question, before continuing: 'I don't believe in any monotheistic human-like super-being orchestrating humanity and creation in moral judgement that determines outcome. I do believe in an organising force that governs nature and all things that can and will be explained scientifically. Metaphysics and spatiality support each other, as far as I'm concerned. I guess I have a different concept of the word spiritual.'

Spirituality, and mysticism in particular, are certainly not foreign concepts to Johnny. In the early 2000s, while recording Boomslang as Johnny Marr + The Healers, he was becoming increasingly interested in esoteric philosophies, immersing himself in books by the likes of George Gurdjieff, P.D. Ouspensky and Helena Blavatsky.

'I was doing a lot of research at that time, studying metaphysics as much as I could. Richard Bucke's Cosmic Consciousness was interesting. The evolution of the human mind... It's a big subject.'

A big subject indeed - but certainly not one beyond the capabilities of Johnny's intellect. This is, after all, a man currently reading Proust, who can quote Kant and Descartes with ease, and who has a comprehensive knowledge of art movements many people wouldn't have even heard of. Johnny Marr is clever - but his is a sort of humble, unpretentious intelligence that exists to benefit his art and his self without the need for attention to be drawn to it for the sake of his ego. There's an element of subtlety to many of his more academic pursuits, particularly when it comes to philosophy.

'I don't think many people know that I have any interests in that area,' he says. 'Perhaps they don't need to.'

Confident yet devoid of egotism, Johnny Marr as an artist is all about progressiveness. He refuses to simply rest on his laurels and stick to a safe, proven formula for success, yet at the same time he's never been outlandishly experimental in his projects just for the sake of it. Although he has changed over the past thirty years (and who hasn't?), it's in a subtle way that suggests a natural shift in personality and interests over time. Evolution, not revolution.

'I don't believe in morphing for the sake of it because that's just contrived,' Johnny states. 'I also hate it when an artist or band who's been around a long time says "I want to be relevant" - it just seems like trying to win over hipsters, and a bit desperate. You have to do what you believe in, no matter what.'

Right now, what Johnny believes in is Playland.

'When I was making The Messenger I realised that I wanted to make another album without waiting too long, so I followed that idea. The success of The Messenger made me even more enthusiastic about doing the follow up, but I'd already started thinking about Playland. I thought it was a good thing to pursue from a creative point of view.'

Asked what he personally perceives to be the fundamental differences between the two albums, Johnny continues: 'I didn't want to change too much. I didn't think I needed to, but it differs in that it's more of a unified sound and lyrical concept whereas The Messenger was more a collection of songs that came together.'

Although generally considered to be his first solo album, The Messenger was not actually Johnny's first foray into being a frontman. Back in 2003, Johnny Marr + The Healers (featuring Johnny as not only lead guitarist, but also lead vocalist and lyricist) released their first and only album, Boomslang - but Johnny insists that The Healers were quite different to his current band with Jack Mitchell (drums), Iwan Gronow (bass) and Doviak (guitar and synths).

'Even though I wrote the songs, there was more of a shared aesthetic that I was representing. The first version of The Healers was a six-piece with synths and percussion and was inspired by very different things to where I'm at now, just because of the passing of time.'

As fate would have it though, it was through The Healers that Johnny first met his closest collaborator, co-producer, friend and band-mate, James Doviak.

'Doviak was running a weird online radio station called Radio Laos, from somewhere outside San Francisco,' Johnny tells me. 'I met him when I was out there promoting Boomslang. He appears to be unapproachable and sinister even, but he's quite nice and he reminds me a bit of Ralf Hütter from Kraftwerk in that regard. He's unusual and a very good musician and he takes care of a lot of technical stuff in the studio, which enables me to concentrate on the guitars and words and concepts. I think it's the longest I've collaborated with anyone.'

As far as words and concepts go, one of the most prevalent themes in Playland is that of architecture: a field Johnny is quite passionately enthusiastic about.

'Buildings do crop up on the album,' he says. 'I like the Modernism movement and how it symbolises the aspirations of the immediate post war period in Europe, before what actually happened from the late seventies onwards - when post-modernism was supposed to be in it's prime, but crappy new towns and bland inner city buildings flew up.'

'The Modernist aesthetic took a massive blow when the agenda of the right- wing administration meant that two bit entrepreneurs with the right contacts threw up cheap faux retro buildings all over the UK,' he adds. 'This kind of character inspired the song "Little King".'

Another song from Playland heavily inspired by architecture is of course second single "Dynamo", which is, by Johnny's own admission, a love song to a building.

'It was inspired by standing beneath a building in Harlem in New York,' Johnny says. 'I was also thinking about the building known as The Gherkin in London, St Mary Axe. I thought it would be good to write a love song and put a different slant on it, so I chose to write a love song to a building. I hoped that people could hear it as a love song to a person and for it to work in that context too.'

Since we're anthropomorphising buildings then, I decide to take a plunge with one of my odder questions: if Playland were a building, what type of structure does Johnny think it would it be?

'I like the idea of Playland as a building,' he agrees, 'Or perhaps a few different types. It's a bit 'Trellick Tower' in places. I spent a lot of time at the South Bank area of the river Thames in London when I was making the album, so if Playland was a building, maybe it would be something along the lines of the Hayward Gallery,' Johnny continues before reaching his final decision: 'I think the Co-Op building at One Angel Square in Manchester would be the one. That would be nice.'

Buildings; places; social situations: these are some of the key inspirations for Johnny's work of late, and so it makes sense that The Situationist International - a group of social revolutionaries in the late 1950s to early 1970s that championed psychogeography as one of their key practices - would also be one of Johnny's influences. 'Like a lot of people, I first became aware of the Situationists from Malcom McLaren's exploits in the Punk days,' Johnny says. 'It was above my head as a schoolboy but I understood their function entirely. Then later I had a few conversations with Tony Wilson about it all, and Guy Debord seemed like someone I should investigate.'

A voracious reader, and particularly well- read in Situationist literature, Johnny even has a book recommendation to share: 'Raoul Vaneigem's Revolution Of Everyday Life is a masterpiece,' he declares. 'It inspired a few things on The Messenger. "The Right Thing Right"...quantity street, etc.'

This is not the first time Johnny has spoken of his interest in and admiration of The Situationists. He readily admits he would love to have been a member of the group himself, had he been old enough back in the 1960s - but concedes that it's unlikely that a similar organisation could still exist and have power in our current times.

'I'd like it think it would be possible to have an organisation like the Situationists, but I doubt it right now,' Johnny states. 'The media have got society so under control that it's hard enough to get attention even when half a million people demonstrate in the streets. Even if it does get attention, that attention gets diverted and diluted so quickly. Trying to subvert in public places seems impossible when you're not even allowed to skateboard in the town centre.'

'Having the Internet could be an advantage of the modern era in subverting the straight world,' he continues, 'But again, the media have gotten very good at convincing people about things. Russell Brand gets so much criticism from people just spouting reactionary rhetoric they've been fed by the media. Some of the people spouting this stuff are young people and therefore should know better. So even if you're saying the obvious on a public forum, you can have it turned on you.'

Another organisation that Johnny is inspired by are the Provos, a group of non-violent anarchists that were active in the Netherlands in the 1960s. 'They had some great ideas,' he enthuses.

While Johnny is too young to have been directly inspired by the Provos and the Situationist International at the height of their powers, other movements have influenced his work by more intimate, firsthand experiences. One such example is Glam (aka glam rock, aka glitter rock); Johnny's first musical love that even now (often subconsciously) manifests itself in his own music. 'Quite a few people said that Easy Money reminded them of Glam,' Johnny says. 'I figured they can't all be wrong and I saw what they meant. It wasn't intentional at all so therefore it's definitely an influence on me no matter what.'

'There have been times when I've consciously taken Glam as an inspiration,' he continues, 'As was the case with "Sheila Take A Bow" or "I Started Something I Couldn't Finish" by The Smiths. Glam was my first musical love. I learned from T.Rex and Sparks and all of it.'

Glam, with all its flamboyancy and camp androgyny, would appear almost the aesthetic inverse of the neat, tailored styles of 1960s mod culture, yet the latter tends to be associated even more closely with Johnny's style - at least by the press.

'It is a bit obvious when I see the "with his mod haircut and jacket" business in press articles,' Johnny concedes before pointing out: 'It's also not accurate.'

'I do of course have a connection with the ideals and style from that period, and I love a lot of the music and Pop Art culture too. There are places where things converge, be it modernist architecture, the French New Wave...all sorts, and I like all of it. Maybe that convergence is in my head. I like to mix it all up.'

Johnny, whose current fashion inspirations are Coco Chanel, The Pistols, the Bloomsbury Set, Christopher Isherwood and Ray Davies circa 1966, is, to quote one of the latter's songs, a dedicated follower of fashion. Onstage he's the epitome of style in fitted blazers, smart button-down shirts and tailored jeans, and his offstage look is no less polished. Though attuned to his own aesthetic and the styles he feels comfortable with, Johnny also acknowledges that there's an increasing quality of aimlessness in the modern fashion world. 'It's possible to have so much choice and variety that there ceases to be direction. I think fashion is in danger of that happening now, if it hasn't happened already.'

'Except beards though,' he adds playfully, 'Which as everyone knows are compulsory.'

Like his music and personality, Johnny's fashion sense has also changed and evolved over the years, but one particular recurring theme is his comfort and willingness to challenge gender norms with his use of accessories. The diamond chandelier necklace of 1984 may now be retired, but he still wears eyeliner - and looks damn good in it. Most recently, it's Johnny's silver nail varnish that has garnered attention from the press and fans alike.

'The nail varnish came about when I was seeing a lot of Kate Nash,' Johnny explains. 'She started putting it on my nails before shows and I kept it. If you can get away with twisting the "guy situation" then do it, even if it spins a few people out - especially if it does, actually,' he adds. 'But not if it looks rubbish.'

'I think choice is an aesthetic decision,' Johnny continues, 'Or can be if you view it that way, and also political in terms of "personal politics", or "politics with a small p". You can buy a pair of jeans for £60 that are okay, or look for a different pair for £60 that you think are more than okay. Why not?'

For Johnny, whose interest in aesthetics extends to the study of it as a branch of philosophy, it's not just about fashion or an image one presents - aestheticism can be a lifestyle.

'I take tea with me into Starbucks and get the water but not the crappy tea,' he explains as an example. 'That's a decision, and a cheaper one usually. It struck me as being aesthetic. This can go on in different areas and to all sorts of degrees. Why not? I was up to a lot of this and then I read Friedrich Schiller's On The Aesthetic Education Of Man. Bingo.'

On the influence of aesthetics in his own art, Johnny says, 'I try to employ it as much as I can. The sleeves are a very obvious example, or my studio space. It's not a requirement, but why not think about the aesthetic if you can?'

This focus on aesthetics also manifests itself in Playland's striking iconography: that of the gyroscope, which is featured not only being held in Johnny's hands on the album cover, but also on one of the album's promotional postcards, and on Jack's drum kit during live shows.

'I had the Gyroscope as something nice to toy around with in the studio. I always liked them when I was younger and I like that it's about conquering or harnessing centrifugal force. That appeals to me,' Johnny explains. 'Then I got very attached to it whilst I was making the album. I found myself messing with it a lot out of habit when I was listening to performances and so on. It was in my pocket when we went out to shoot the cover, so it seemed fitting that I was holding it on the cover.'

'Someone pointed out to me that both album covers have the aspect of being unbalanced on them. That was unintentional, but it's interesting.'

While many of his current and upcoming projects are still musical - a Depeche Mode cover on limited edition 7" vinyl for Record Store Day; an upcoming live LP, and of course continued touring - Johnny isn't ruling out other non-musical pursuits in addition to the autobiography that's scheduled for release next year. Acting ('I would do a film if it was the right part') and creative writing ('I have a book or two in me if I get around to it') are future possibilities, although an LP consisting entirely of tracks recorded on the theremin will have to remain one of this interviewer's unrealised dreams ('I was just being silly', Johnny admits). Although very content with what he's doing now, Johnny has the courage and confidence to not hold back from projects just because it's not what other people expect of him.

'If I was excited about doing something with a completely different direction and totally believed it was right, I would do it without hesitation,' he affirms.

One gets the impression that Johnny Marr is a man who enjoys keeping busy, and more importantly, being productive. Would too much "downtime" therefore leave such an active and energetic man frustrated and restless?

'I can't imagine having nothing to do,' Johnny says. 'There's always something going on. Would I get restless?' he muses. 'Maybe I would. Something would happen.'

One last question then, before leaving our ever-obliging hero to get on with his day's tasks: If it turned out tomorrow that there was absolutely no work to do, and Johnny were expected to devote it entirely to leisure pursuits, what would he spend the day doing?

'Is watching the entire history of cinema a leisure pursuit?' he asks. 'Either that or become the greatest ever Englishman of the Trampoline...'

There's never a need to worry about awkward silences when talking to Johnny. He can articulately converse for hours on topics as wide-ranging as music, philosophy, politics ('with a small p'), art and literature, and is never, ever boring. Not only does he like to talk, but he's bloody good at it. 'I don't think anyone's as good at anything as I am at talking,' Johnny says playfully, a cheeky grin lighting up his handsome features. And he could very well be right.

Despite having spent more than thirty years in the spotlight now, and given countless interviews, Johnny exhibits very little hostility towards the press. 'I think I get a fair enough shake,' he concedes. 'But most people I talk to are alright and the solo records have been very well received, so I don't have a problem. Some journalists can come with an agenda and think they're going to get under my skin by asking about The Smiths and therefore get some kind of scoop or something, but that would be flattering themselves. It doesn't happen too much.'

Both Playland and its precursor The Messenger have been met with overwhelmingly positive reactions from the press, and the past few years since launching his solo career have seen journalists the world over clamouring for a chat with the iconic Mancunian guitarist. For Johnny though, the opinions that matter most are that of his own fan base.

'I want my audience to like what I put out,' he says. 'That sounds very obvious, but it doesn't have to be an automatic consideration for a band or artist. You could have a different agenda.'

'I like my audience,' Johnny continues. 'It's interesting to me to know what some of them do and what they're about sometimes. Social Media is somewhat of a mixed bag - it's not all good news, but I've had some nice experiences and that's been cool. Also, what's the alternative to being nice to fans...being nasty? That doesn't sit right with me. Never has. I've always thought the fans were really important.'

'There are things that happen that are very touching. I've had people make marriage proposals during the show, and there's a young guy with autism who comes to hang out with us sometimes. He gets on Jack's kit at soundchecks and the pleasure he gets from that is really nice to see. Having someone name their child after you is a real honour, of course. There are a lot of people with "There Is A Light That Never Goes Out" on their bodies, and I'm amazed when people get a picture of me tattooed on themselves. Some people travel from all over the world. Mostly, I like to see people losing themselves in the show. That's the best thing.'

"I like my audience. It's interesting to me to know what some of them do and what they're about . . . . I've always thought the fans were really important."

Johnny's audience is an interesting mix. Some are veteran Smiths fans who have followed his career right from the start; others have been introduced to Johnny's music through more recent former bands such as Modest Mouse and The Cribs. Another even newer category of fans are young people who have been initiated into the World Of Marr through his recent solo records: those who know him first and foremost as "Johnny Marr", not "Johnny Marr of The Smiths", although many go on to discover much of his back catalogue as well.

'It's really touching and gratifying to see very young people at the shows,' Johnny says. 'They're usually there totally because they love the music, all of it. It doesn't matter how they got into it, and there's all kinds of reasons, but it's definitely not because of some hype. It's always a personal connection of some sort to the music or to me, so that's quite special.'

Inevitably, Johnny has attracted his fair share of youthful admirers. It's an everyday occurrence to see young (often - but not always - female) fans expressing declarations of romantic attraction towards the 51-year-old guitarist via social media, and quite frequently even in messages directed at Johnny himself. Though other artists in his position might feel somewhat uncomfortable with being seen as an object of desire in the eyes of people even younger than his own children, Johnny is refreshingly unperturbed. 'I just put it down as an aspect of fame, people projecting things, for whatever reason,' he explains. 'I've never analysed that. It's beyond analysis, really.'

Beyond analysis such things may be, but being able to relate to his audience, regardless of their age, gender or lifestyle, seems of paramount importance to Johnny.

'I like to think that my audience have some of the same sensibilities. I realise that from a young age I've lived a very different life to most people, but people's values can be alike, even if it's just musically. I think the audience know my ideology,' Johnny says, although he also makes a point to explain: 'I don't mind if people just like me for my guitar playing though. That's fine. I'm happy that the fans like what I do for whatever reason they like.'

'I will say this though,' he adds. 'I don't think the lyrics are obscure. Far from it. I just don't go around advertising the concepts.'

As a solo artist, Johnny has proven himself to be more than just a gifted guitarist and composer: he's also a talented lyricist, whose words are profound and poetic without resorting to the sort of clicheéd, self-indulgent omphaloskepsis that seems to be in vogue with the current indie crowd. Johnny's lyrics tend to be inspired by observation rather than introspection, and as a result his sources for inspiration are practically infinite. Heightened imagination, he says, is the primary benefit of choosing to write about external situations rather than his own emotions.

'There's more for me to imagine than if I'm expressing my own feelings. Ultimately whatever you write is a reflection of yourself and how you perceive things. I'm not particularly interested in expressing my opinions as such at this point, and everyone seems to be doing that. I'd rather observe external things. Someone has to do it.'

'I like to make the lyrics more observational than introspective,' he continues. 'I'm usually on alert for inspiration and sometimes something might jump out at me from a conversation between people, or an article somewhere about something. It's enjoyable when I'm not looking and a phrase or word or concept surprises me. Inspiration doesn't strike so much if you're trying too hard. It's what artists need to live.'

One particular recurring concept in Johnny's lyrics is that of escapism. Escapism through music; through technology; through sex. Even beyond Johnny's lyrics, it's a theme so strong and so prevalent that it can't help but make one question: what is it that so many people are trying to escape from? And where are they hoping to escape to?

'Chasing after escapism through entertainment, consumerism and physical sensation, amongst other things, seems to be the social norm,' Johnny explains. 'Entertainment through the big night out, consumerism through rinsing the credit card and physical sensation through alcohol culture or sexual preoccupation is always there. I'm a product of the culture myself and I'm involved the same as everyone,' he acknowledges, 'So I'm not judging. But I'm wondering if it's because we've stopped knowing how to be with ourselves? Maybe people aren't okay with themselves. Even if you're self-aware you can still suffer a certain malaise, which is what "This Tension" is about. I did think it was important to celebrate escapism though, in songs like "Back In The Box" and "Playland", to express the other side of it. Those songs are tributes to transcendence, mostly through music and sex.'

"Inspiration doesn't strike so much if you're trying too hard. It's what artists need to live."

Hearing him speak so articulately about his ideas and inspirations, it comes as no surprise when Johnny admits he's been writing lyrics almost all his life.

'I started writing lyrics when I was about fourteen or fifteen,' he tells me. 'The first lyrics I wrote when I was ten or eleven, but I think they might have been a bit immature. I never didn't write entirely. Even in The Smiths I wrote bits of prose sometimes, just for myself.'

Intrigued, I ask what was the first song Johnny ever wrote a full set of lyrics to.

'That would've been when I was eleven, for my first band. I don't remember the title but it was about not liking school and getting the hell out. Some things don't change, thank god.'

Interestingly, it was those schooldays that inspired Johnny's most autobiographical song to date. "25 Hours", with lyrics such as 'And the heat and the bricks / Were falling on me like doom', paints an understandably bleak picture of not only education in Manchester in the 1970s, but the brutality of the Catholic church.

'The Catholic religion hasn't exactly made itself very credible over the last twenty five years or so, has it?' Johnny muses. 'Anyone who was brought up around priests and nuns will tell you it was sadistic, and worse.'

His feelings about Catholicism quite clear, I'm admittedly curious to know: Does Johnny Marr believe in God?

'Bloody hell,' is his initial response to such a question, before continuing: 'I don't believe in any monotheistic human-like super-being orchestrating humanity and creation in moral judgement that determines outcome. I do believe in an organising force that governs nature and all things that can and will be explained scientifically. Metaphysics and spatiality support each other, as far as I'm concerned. I guess I have a different concept of the word spiritual.'

Spirituality, and mysticism in particular, are certainly not foreign concepts to Johnny. In the early 2000s, while recording Boomslang as Johnny Marr + The Healers, he was becoming increasingly interested in esoteric philosophies, immersing himself in books by the likes of George Gurdjieff, P.D. Ouspensky and Helena Blavatsky.

'I was doing a lot of research at that time, studying metaphysics as much as I could. Richard Bucke's Cosmic Consciousness was interesting. The evolution of the human mind... It's a big subject.'

A big subject indeed - but certainly not one beyond the capabilities of Johnny's intellect. This is, after all, a man currently reading Proust, who can quote Kant and Descartes with ease, and who has a comprehensive knowledge of art movements many people wouldn't have even heard of. Johnny Marr is clever - but his is a sort of humble, unpretentious intelligence that exists to benefit his art and his self without the need for attention to be drawn to it for the sake of his ego. There's an element of subtlety to many of his more academic pursuits, particularly when it comes to philosophy.

'I don't think many people know that I have any interests in that area,' he says. 'Perhaps they don't need to.'

Confident yet devoid of egotism, Johnny Marr as an artist is all about progressiveness. He refuses to simply rest on his laurels and stick to a safe, proven formula for success, yet at the same time he's never been outlandishly experimental in his projects just for the sake of it. Although he has changed over the past thirty years (and who hasn't?), it's in a subtle way that suggests a natural shift in personality and interests over time. Evolution, not revolution.

'I don't believe in morphing for the sake of it because that's just contrived,' Johnny states. 'I also hate it when an artist or band who's been around a long time says "I want to be relevant" - it just seems like trying to win over hipsters, and a bit desperate. You have to do what you believe in, no matter what.'

Right now, what Johnny believes in is Playland.

'When I was making The Messenger I realised that I wanted to make another album without waiting too long, so I followed that idea. The success of The Messenger made me even more enthusiastic about doing the follow up, but I'd already started thinking about Playland. I thought it was a good thing to pursue from a creative point of view.'

"I don't believe in morphing for the sake of it because that's just contrived. You have to do what you believe in, no matter what."

Asked what he personally perceives to be the fundamental differences between the two albums, Johnny continues: 'I didn't want to change too much. I didn't think I needed to, but it differs in that it's more of a unified sound and lyrical concept whereas The Messenger was more a collection of songs that came together.'

Although generally considered to be his first solo album, The Messenger was not actually Johnny's first foray into being a frontman. Back in 2003, Johnny Marr + The Healers (featuring Johnny as not only lead guitarist, but also lead vocalist and lyricist) released their first and only album, Boomslang - but Johnny insists that The Healers were quite different to his current band with Jack Mitchell (drums), Iwan Gronow (bass) and Doviak (guitar and synths).

'Even though I wrote the songs, there was more of a shared aesthetic that I was representing. The first version of The Healers was a six-piece with synths and percussion and was inspired by very different things to where I'm at now, just because of the passing of time.'

As fate would have it though, it was through The Healers that Johnny first met his closest collaborator, co-producer, friend and band-mate, James Doviak.

'Doviak was running a weird online radio station called Radio Laos, from somewhere outside San Francisco,' Johnny tells me. 'I met him when I was out there promoting Boomslang. He appears to be unapproachable and sinister even, but he's quite nice and he reminds me a bit of Ralf Hütter from Kraftwerk in that regard. He's unusual and a very good musician and he takes care of a lot of technical stuff in the studio, which enables me to concentrate on the guitars and words and concepts. I think it's the longest I've collaborated with anyone.'

As far as words and concepts go, one of the most prevalent themes in Playland is that of architecture: a field Johnny is quite passionately enthusiastic about.

'Buildings do crop up on the album,' he says. 'I like the Modernism movement and how it symbolises the aspirations of the immediate post war period in Europe, before what actually happened from the late seventies onwards - when post-modernism was supposed to be in it's prime, but crappy new towns and bland inner city buildings flew up.'

'The Modernist aesthetic took a massive blow when the agenda of the right- wing administration meant that two bit entrepreneurs with the right contacts threw up cheap faux retro buildings all over the UK,' he adds. 'This kind of character inspired the song "Little King".'

Another song from Playland heavily inspired by architecture is of course second single "Dynamo", which is, by Johnny's own admission, a love song to a building.

'It was inspired by standing beneath a building in Harlem in New York,' Johnny says. 'I was also thinking about the building known as The Gherkin in London, St Mary Axe. I thought it would be good to write a love song and put a different slant on it, so I chose to write a love song to a building. I hoped that people could hear it as a love song to a person and for it to work in that context too.'

Since we're anthropomorphising buildings then, I decide to take a plunge with one of my odder questions: if Playland were a building, what type of structure does Johnny think it would it be?

'I like the idea of Playland as a building,' he agrees, 'Or perhaps a few different types. It's a bit 'Trellick Tower' in places. I spent a lot of time at the South Bank area of the river Thames in London when I was making the album, so if Playland was a building, maybe it would be something along the lines of the Hayward Gallery,' Johnny continues before reaching his final decision: 'I think the Co-Op building at One Angel Square in Manchester would be the one. That would be nice.'

Buildings; places; social situations: these are some of the key inspirations for Johnny's work of late, and so it makes sense that The Situationist International - a group of social revolutionaries in the late 1950s to early 1970s that championed psychogeography as one of their key practices - would also be one of Johnny's influences. 'Like a lot of people, I first became aware of the Situationists from Malcom McLaren's exploits in the Punk days,' Johnny says. 'It was above my head as a schoolboy but I understood their function entirely. Then later I had a few conversations with Tony Wilson about it all, and Guy Debord seemed like someone I should investigate.'

A voracious reader, and particularly well- read in Situationist literature, Johnny even has a book recommendation to share: 'Raoul Vaneigem's Revolution Of Everyday Life is a masterpiece,' he declares. 'It inspired a few things on The Messenger. "The Right Thing Right"...quantity street, etc.'

This is not the first time Johnny has spoken of his interest in and admiration of The Situationists. He readily admits he would love to have been a member of the group himself, had he been old enough back in the 1960s - but concedes that it's unlikely that a similar organisation could still exist and have power in our current times.

'I'd like it think it would be possible to have an organisation like the Situationists, but I doubt it right now,' Johnny states. 'The media have got society so under control that it's hard enough to get attention even when half a million people demonstrate in the streets. Even if it does get attention, that attention gets diverted and diluted so quickly. Trying to subvert in public places seems impossible when you're not even allowed to skateboard in the town centre.'

'Having the Internet could be an advantage of the modern era in subverting the straight world,' he continues, 'But again, the media have gotten very good at convincing people about things. Russell Brand gets so much criticism from people just spouting reactionary rhetoric they've been fed by the media. Some of the people spouting this stuff are young people and therefore should know better. So even if you're saying the obvious on a public forum, you can have it turned on you.'

"The media have got society so under control that it's hard enough

to get attention even when half a million people demonstrate in the streets. Even if it does get attention, that attention gets diverted and diluted so quickly. Trying to subvert in public places seems impossible when you're not even allowed to skateboard in the town centre."

Another organisation that Johnny is inspired by are the Provos, a group of non-violent anarchists that were active in the Netherlands in the 1960s. 'They had some great ideas,' he enthuses.

While Johnny is too young to have been directly inspired by the Provos and the Situationist International at the height of their powers, other movements have influenced his work by more intimate, firsthand experiences. One such example is Glam (aka glam rock, aka glitter rock); Johnny's first musical love that even now (often subconsciously) manifests itself in his own music. 'Quite a few people said that Easy Money reminded them of Glam,' Johnny says. 'I figured they can't all be wrong and I saw what they meant. It wasn't intentional at all so therefore it's definitely an influence on me no matter what.'

'There have been times when I've consciously taken Glam as an inspiration,' he continues, 'As was the case with "Sheila Take A Bow" or "I Started Something I Couldn't Finish" by The Smiths. Glam was my first musical love. I learned from T.Rex and Sparks and all of it.'

Glam, with all its flamboyancy and camp androgyny, would appear almost the aesthetic inverse of the neat, tailored styles of 1960s mod culture, yet the latter tends to be associated even more closely with Johnny's style - at least by the press.

'It is a bit obvious when I see the "with his mod haircut and jacket" business in press articles,' Johnny concedes before pointing out: 'It's also not accurate.'

'I do of course have a connection with the ideals and style from that period, and I love a lot of the music and Pop Art culture too. There are places where things converge, be it modernist architecture, the French New Wave...all sorts, and I like all of it. Maybe that convergence is in my head. I like to mix it all up.'

Johnny, whose current fashion inspirations are Coco Chanel, The Pistols, the Bloomsbury Set, Christopher Isherwood and Ray Davies circa 1966, is, to quote one of the latter's songs, a dedicated follower of fashion. Onstage he's the epitome of style in fitted blazers, smart button-down shirts and tailored jeans, and his offstage look is no less polished. Though attuned to his own aesthetic and the styles he feels comfortable with, Johnny also acknowledges that there's an increasing quality of aimlessness in the modern fashion world. 'It's possible to have so much choice and variety that there ceases to be direction. I think fashion is in danger of that happening now, if it hasn't happened already.'

'Except beards though,' he adds playfully, 'Which as everyone knows are compulsory.'

Like his music and personality, Johnny's fashion sense has also changed and evolved over the years, but one particular recurring theme is his comfort and willingness to challenge gender norms with his use of accessories. The diamond chandelier necklace of 1984 may now be retired, but he still wears eyeliner - and looks damn good in it. Most recently, it's Johnny's silver nail varnish that has garnered attention from the press and fans alike.

'The nail varnish came about when I was seeing a lot of Kate Nash,' Johnny explains. 'She started putting it on my nails before shows and I kept it. If you can get away with twisting the "guy situation" then do it, even if it spins a few people out - especially if it does, actually,' he adds. 'But not if it looks rubbish.'

'I think choice is an aesthetic decision,' Johnny continues, 'Or can be if you view it that way, and also political in terms of "personal politics", or "politics with a small p". You can buy a pair of jeans for £60 that are okay, or look for a different pair for £60 that you think are more than okay. Why not?'

For Johnny, whose interest in aesthetics extends to the study of it as a branch of philosophy, it's not just about fashion or an image one presents - aestheticism can be a lifestyle.

'I take tea with me into Starbucks and get the water but not the crappy tea,' he explains as an example. 'That's a decision, and a cheaper one usually. It struck me as being aesthetic. This can go on in different areas and to all sorts of degrees. Why not? I was up to a lot of this and then I read Friedrich Schiller's On The Aesthetic Education Of Man. Bingo.'

On the influence of aesthetics in his own art, Johnny says, 'I try to employ it as much as I can. The sleeves are a very obvious example, or my studio space. It's not a requirement, but why not think about the aesthetic if you can?'

This focus on aesthetics also manifests itself in Playland's striking iconography: that of the gyroscope, which is featured not only being held in Johnny's hands on the album cover, but also on one of the album's promotional postcards, and on Jack's drum kit during live shows.

'I had the Gyroscope as something nice to toy around with in the studio. I always liked them when I was younger and I like that it's about conquering or harnessing centrifugal force. That appeals to me,' Johnny explains. 'Then I got very attached to it whilst I was making the album. I found myself messing with it a lot out of habit when I was listening to performances and so on. It was in my pocket when we went out to shoot the cover, so it seemed fitting that I was holding it on the cover.'

'Someone pointed out to me that both album covers have the aspect of being unbalanced on them. That was unintentional, but it's interesting.'

While many of his current and upcoming projects are still musical - a Depeche Mode cover on limited edition 7" vinyl for Record Store Day; an upcoming live LP, and of course continued touring - Johnny isn't ruling out other non-musical pursuits in addition to the autobiography that's scheduled for release next year. Acting ('I would do a film if it was the right part') and creative writing ('I have a book or two in me if I get around to it') are future possibilities, although an LP consisting entirely of tracks recorded on the theremin will have to remain one of this interviewer's unrealised dreams ('I was just being silly', Johnny admits). Although very content with what he's doing now, Johnny has the courage and confidence to not hold back from projects just because it's not what other people expect of him.

'If I was excited about doing something with a completely different direction and totally believed it was right, I would do it without hesitation,' he affirms.

One gets the impression that Johnny Marr is a man who enjoys keeping busy, and more importantly, being productive. Would too much "downtime" therefore leave such an active and energetic man frustrated and restless?

'I can't imagine having nothing to do,' Johnny says. 'There's always something going on. Would I get restless?' he muses. 'Maybe I would. Something would happen.'

One last question then, before leaving our ever-obliging hero to get on with his day's tasks: If it turned out tomorrow that there was absolutely no work to do, and Johnny were expected to devote it entirely to leisure pursuits, what would he spend the day doing?

'Is watching the entire history of cinema a leisure pursuit?' he asks. 'Either that or become the greatest ever Englishman of the Trampoline...'

Interview & photos by Aly Stevenson. Originally published in issue #3 of our fanzine, Dynamic.